It feels like every other month, I’m encountering another photographic technique—either at the point of capture, or at the point of development—and this is my attempt to begin to collate a few I find particularly interesting. I love how there’s a folklore to it; you’re going to find these examples strewn across various corners of the Internet and in the world. Many of these techniques are simply the result of people messing around with their process and deciding they like the result, forming such original pieces of art that the process is often eponymous.

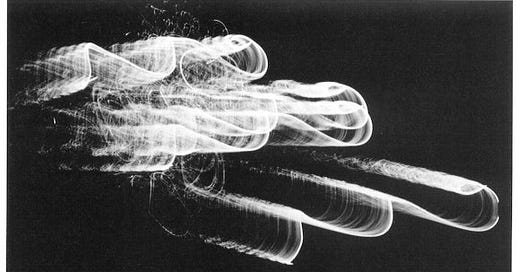

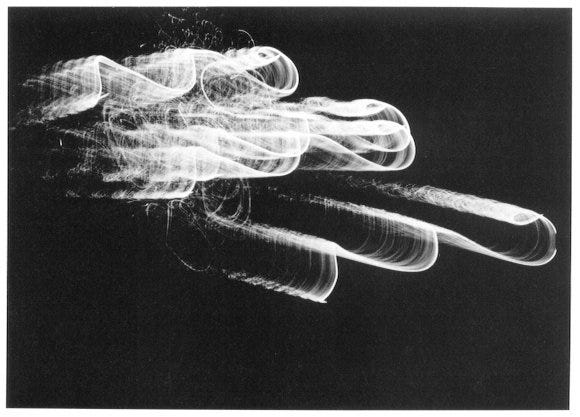

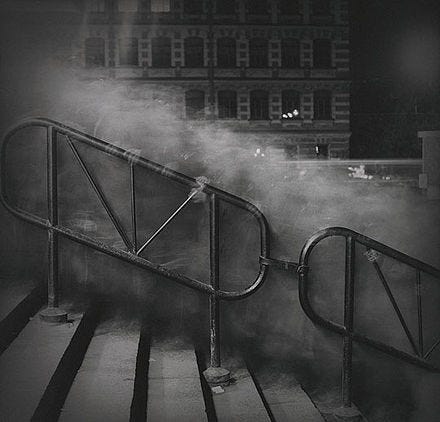

The one I’ve applied the most in my work so far is Intentional Camera Movement (ICM). It’s exactly as it sounds, and can produce all kinds of beautiful blur effects that, to me, feel honest and accurate in the sense that the image is still the result of holistically capturing a collection of light through time. Examples of ICM in the film-only era don’t seem to be that common—which seems fair because the process is counterintuitive, film is relatively precious, and the results are nothing if not a bit spastic. Kōtarō Tanaka’s fireworks photography from the 1960s is cited as an early example; it’s beautiful stuff. Alexey Titatenko’s work is one of the earlier and better known examples of ICM in effective use in street photography.

I’ve also come across the so-called Adamski blur; Josh Adamski uses layers in Photoshop to achieve ICM-like aspects that are impossible to capture in-camera. I’m less convinced by this technique, personally—it feels over done and the illusion doesn’t hit for me, since I can’t suspend my disbelief. Though I believe these draw more attention to its process than the result itself, it’s worth mentioning. (If I’ve learned anything about making photographs, it’s that the process matters.)

A more subtle composite effect is known as the Orton effect. Named after Canadian landscape photographer Michael Orton and developed in the mid-1980s, it’s a kind of organic HDR (high dynamic range)—with multiple exposures of the same scene, typically capturing different exposure levels, to create a dreamy result as the details might not quite match up. It introduces a question for me—when is a composite no longer representative of a moment? For me, Orton effect images and Brenizer photos (to be discussed), pass the bar well enough.

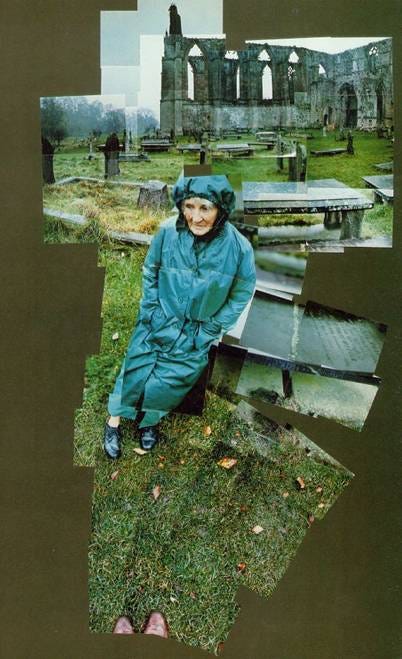

The 1980s were a rich period for photographic experimentation. As Orton was creating vertically stacked composites, David Hockney was busy cobbling together “joiners”. The idea is to blow up the notion of panoramic perfection, creating a composite of photos joined loosely, wherever they may land. It both abstracts and offers greater detail on the subject, expanding the capacity of the lens over space and time.

On the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum for stitched panoramas would probably be the Brenizer method, popularized (but not coined) by New York wedding photographer Ryan Brenizer in 2008. My feeling is that there was a perfect storm of factors that led to its picking up; film was on the wane (though it now stays afloat with its ballast of ardent fans, like vinyl) and with digital that meant giving up the larger size of 120 film. That also means, effectively, a loss in the unique visual characteristics of medium and larger formats: a good about of compression, coupled with a wider field of view, and spectacular bokeh due to the thinner depth of field afforded by larger formats, all else (aperture, distance to subject, focal length) being equal. So what Brenizer did was recreate that larger format by shooting all around a subject—typically a posed portrait, as action shots aren’t going to work—and it handily achieves its goals.

Stepping back a bit (okay, way back—late 1800s) into the film-only era, various chemical and physical interventions at the taking, development, and printing stages can also deeply inform the art. Mordançage, for example, sees the photographer physically lift and reposition the darker portions of a print, altering the entire image. Polaroid emulsion lifts offer a similar idea in terms of physical repositioning.

Not necessarily ultimately altering the result, but certainly worth a mention, is the practice of ruh khitch, or “spirit-pulling” (Punjabi), which integrates the darkroom and camera in a single apparatus. Practiced in South Asia and Cuba, it’s named as such for the unique way (especially before 1948’s Land camera) in which the photographer can deliver a positive image within minutes of taking the photograph. No doubt the availability and convenience of this process impacted the kind of images that were taken.

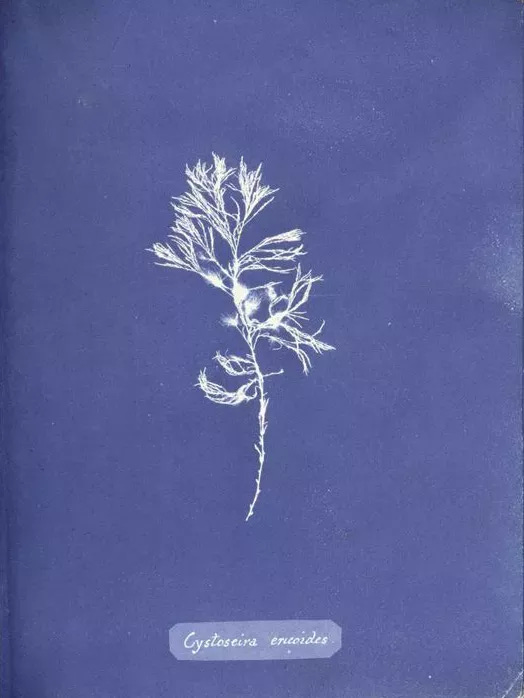

Compressing the process of light to image even further was of course the Man Ray’s Rayograph, the result of objects placed directly on light-sensitive paper with no lens or box as an intermediary, much like cyanotypes. It’s thanks to Anna Atkins and the cyanotype process that the world received the first photographically illustrated book, British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, in 1853.

When I briefly survey the history of photographic techniques like this, I wonder what I’m missing and whose histories of photographic innovation and experimentation are being omitted. I can’t help but notice most of the names above aren’t terribly diverse. Surely others have been doing the same things contemporaneously, but personally, I haven’t been able to find many examples. This is something I hope to learn more about going forward.